Appearance

Mastering Strategic Domain Driven Design: Sculpting Resilience with Bounded Contexts and Context Mapping

Before we lay a single line of code, let's sketch the blueprint. Today, we're not just coding, we're sculpting a resilient, scalable future—one well-designed service at a time. In the realm of complex software systems, Domain Driven Design (DDD) offers a powerful lens through which to view and manage this complexity. While many discussions around DDD focus on tactical patterns like Aggregates and Entities, the true architectural power lies in its strategic design principles. This article will deep dive into the critical concepts of Bounded Contexts and Context Mapping, showing how they form the bedrock for building maintainable and adaptable distributed systems.

The Heart of Complexity: Why Strategic Design is Paramount

Modern applications often deal with vast, interconnected business domains. Without clear architectural guidance, these domains can become tangled messes, leading to:

- Ambiguous Language: Different teams using the same terms to mean different things, leading to miscommunication and bugs.

- Tight Coupling: Changes in one part of the system unexpectedly breaking another.

- Scalability Challenges: Difficulty in scaling individual components due to shared codebases or databases.

- Cognitive Overload: Developers struggling to grasp the entire system's logic.

Strategic DDD addresses these challenges head-on by providing tools to break down a large system into smaller, more manageable parts that can evolve independently. This is where Bounded Contexts shine.

Bounded Contexts: Defining Your Domain's Boundaries 🏗️

A Bounded Context is a central pattern in strategic Domain Driven Design. It defines a specific area within your overall system where a particular domain model is clear, consistent, and applies without ambiguity. Think of it as a distinct universe where specific terms and rules hold true.

In different parts of a business, the same word can have different meanings. For instance, a "Customer" in a Sales Bounded Context might mean someone with a billing address and purchasing history, while a "Customer" in a Support Bounded Context might refer to someone with open support tickets and interaction history. These are two different models of a customer, each valid within its own context.

Key Characteristics of a Bounded Context:

- Ubiquitous Language: Each Bounded Context has its own Ubiquitous Language, a shared vocabulary used by both domain experts and developers within that specific context. This language is precise and consistent, eliminating misunderstandings.

- Explicit Boundaries: The boundaries of a Bounded Context are explicit. What belongs inside is clear, and what doesn't is outside.

- Independent Model: The domain model within a Bounded Context is self-contained and consistent. It doesn't need to be consistent with models in other contexts in the same way.

- Team Ownership: Often, a Bounded Context aligns with the scope of a single team, fostering autonomy and clear ownership.

Ubiquitous Language: Speaking the Same Language Within a Context

Within each Bounded Context, the Ubiquitous Language is paramount. It's not just jargon; it's the precise, consistent language agreed upon by developers and domain experts. This language is refined iteratively as the team gains a deeper understanding of the domain.

For example, consider an e-commerce system:

- In the

Order Fulfillmentcontext, "Shipment" might refer to the physical package being sent, with specific statuses likepacked,shipped,delivered. - In the

Inventory Managementcontext, "Shipment" could refer to a delivery of goods from a supplier, with statuses likereceived,inspected.

These are distinct concepts, and the Ubiquitous Language helps ensure everyone working within a specific Bounded Context understands and uses terms consistently.

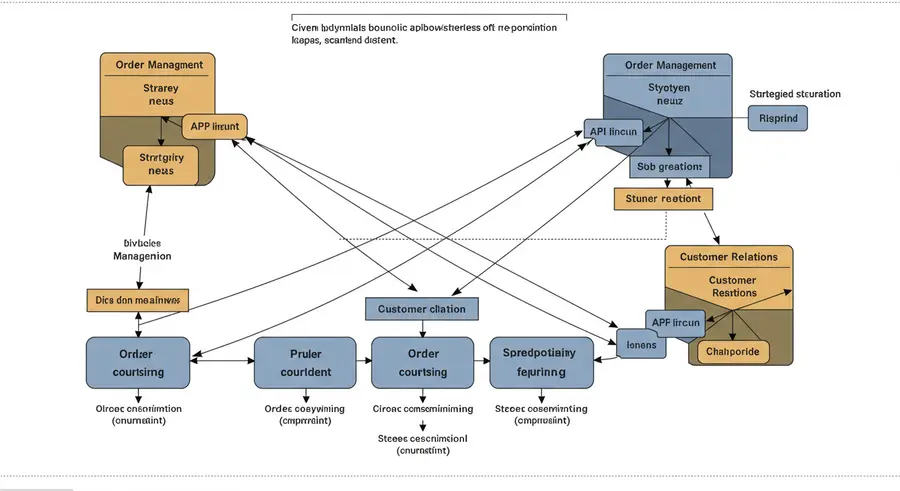

Context Mapping: Understanding Relationships Between Contexts 🔗

While Bounded Contexts define independent universes, real-world systems are rarely isolated. Context Mapping is the process of explicitly defining the relationships between different Bounded Contexts. This helps manage integration points and understand dependencies.

There are several standard patterns for Context Mapping:

- Partnership: Two teams collaborate closely on shared functionality, with success dependent on mutual understanding and effort. Changes in one context require coordination with the other.

- Shared Kernel: A subset of the domain model that two or more Bounded Contexts share. This is usually code (e.g., a shared library) that both teams agree to change together.

- Customer/Supplier: One Bounded Context (the upstream "Supplier") provides a service or data to another Bounded Context (the downstream "Customer"). The Supplier team has influence over the Customer's success. The Customer can try to influence the Supplier's roadmap, but ultimately the Supplier defines the API.

- Conformist: Similar to Customer/Supplier, but the downstream team (Conformist) simply conforms to the upstream team's model, even if it's not ideal for their context. They have no influence over the upstream. This often happens when integrating with off-the-shelf software or external systems.

- Anti-Corruption Layer (ACL): A protective layer built by the downstream context to translate the model of an upstream system into its own Ubiquitous Language. This shields the downstream context from changes in the upstream system, preventing contamination of its own domain model. This is crucial for integrating with legacy systems or third-party APIs.

- Separate Ways: The teams decide that the integration cost is too high, and they deliberately choose to have no direct communication or integration between their contexts, even if there's overlapping domain functionality. They simply "go separate ways."

Understanding these relationships is vital for managing dependencies, planning integrations, and identifying potential friction points in a distributed system.

Practical Application: Identifying and Defining Bounded Contexts

So, how do you identify Bounded Contexts in your system?

- Start with the Business Domain: Engage with domain experts. What are the core business capabilities? What are the key processes?

- Identify Language Inconsistencies: Where do terms have different meanings? These are strong indicators of potential Bounded Context boundaries.

- Look for Organizational Structure: Conway's Law often suggests that software architecture mirrors organizational structure. Teams often align with Bounded Contexts.

- Consider Independent Change: Which parts of the system need to evolve independently?

- Event Storming: This collaborative workshop technique is excellent for discovering domain events and identifying Bounded Contexts.

Once identified, diagram these contexts and their relationships using Context Mapping. This visual representation becomes a powerful tool for communication and strategic planning.

Benefits of Strategic DDD ☁️✨

Adopting strategic Domain Driven Design brings significant advantages:

- Reduced Complexity: Breaking down a monolithic domain into manageable, self-contained parts.

- Improved Scalability: Individual Bounded Contexts can be developed, deployed, and scaled independently (often aligning with microservices architectures).

- Enhanced Maintainability: Clear boundaries and dedicated teams lead to more focused and understandable codebases.

- Better Business Alignment: Software truly reflects the business domain, fostering closer collaboration between technical and business teams.

- Increased Team Autonomy: Teams can innovate and iterate faster within their own contexts.

Challenges and Considerations

While powerful, strategic DDD isn't a silver bullet:

- Initial Overhead: Identifying contexts and defining ubiquitous languages requires significant upfront collaboration and domain expertise.

- Integration Complexity: While Context Mapping clarifies relationships, managing integrations (especially with Anti-Corruption Layers) adds complexity.

- Data Consistency: Achieving eventual consistency across distributed Bounded Contexts requires careful design (e.g., using event-driven architectures).

Conclusion: Sculpting a Better Future with Domain Driven Design

Domain Driven Design, especially its strategic aspects, provides a robust framework for managing complexity in modern software systems. By rigorously defining Bounded Contexts and explicitly mapping their relationships, we can create architectures that are not only functional but also resilient, scalable, and genuinely aligned with business needs. It's about designing for growth from the outset, rather than patching problems post-launch.

Embrace strategic DDD to architect for tomorrow, and build for today—sculpting resilience, one service at a time.

References & Further Reading

- Eric Evans' "Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software": The foundational text for DDD.

- Vaughn Vernon's "Implementing Domain-Driven Design": A practical guide to implementing DDD concepts.

- Mastering Strategic Design in Domain-Driven Design (DDD): A Deep Dive: A good overview of strategic design.

- Domain-Driven Design and Development In Practice - InfoQ: Practical insights into DDD implementation.